Next: 4a: Practical debugging part I - Processes

3: Windows (nt) Architecture

In this part I will introduce several windows concepts that will be required to understand the next tutorials. If you get bored just continue with hands-on windows internals in Part4a: Processes and come back later.

Many of these concepts have been introduces with Windows NT and have been around for centuries. Some of them, like the whole kernel-user space distinction and syscalls are not even specific to Windows. I will still try my best to keep everything as current (Windows 10) as possible.

Syscalls?

I mentioned syscalls already so it is about time we did a quick recap on what those are.

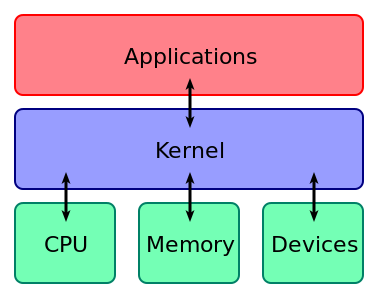

Operating systems do a lot. And really complicated sh** too. But if you ignore the details it's really just a middleware between the hardware and whatever the user wants to do. Like on this picture I borrowed from the wikipedia page about the kernel, the core part of the operating system:

So for instance the operation system could export a function called osReadFile to access the hard drive. Every time something running on this operating system needs to read from a file it would call that function. A "call to the operation system", or short: syscall. And if you where to design a simple embedded system, like a portable music player your operating system could really be just that: a bunch of special functions between your feature code and your hardware.

Of course on a real computer and nowadays that category pretty much starts at portable music players you can't do it like that. Any hope of security or system stability would go right out of the windows if any random programmer would have direct access to important operating system functionality.

So on Windows you can't just call nt!NtCreateUserProcess. This is enforced by the CPU and you can't argue with the CPU ((Well.. with Spectre and Meltdown you sort of can, that's why they are so scary.)) The x64 CPU offers four modes, called rings that are designed to completely separate privilege levels. Windows uses two of these - ring 0 for the kernel and ring 3 for user mode - and the only way to switch between them is via a special syscall mechanism. It's actually the same for Linux just the actual implementation is different.

Windows Architecture

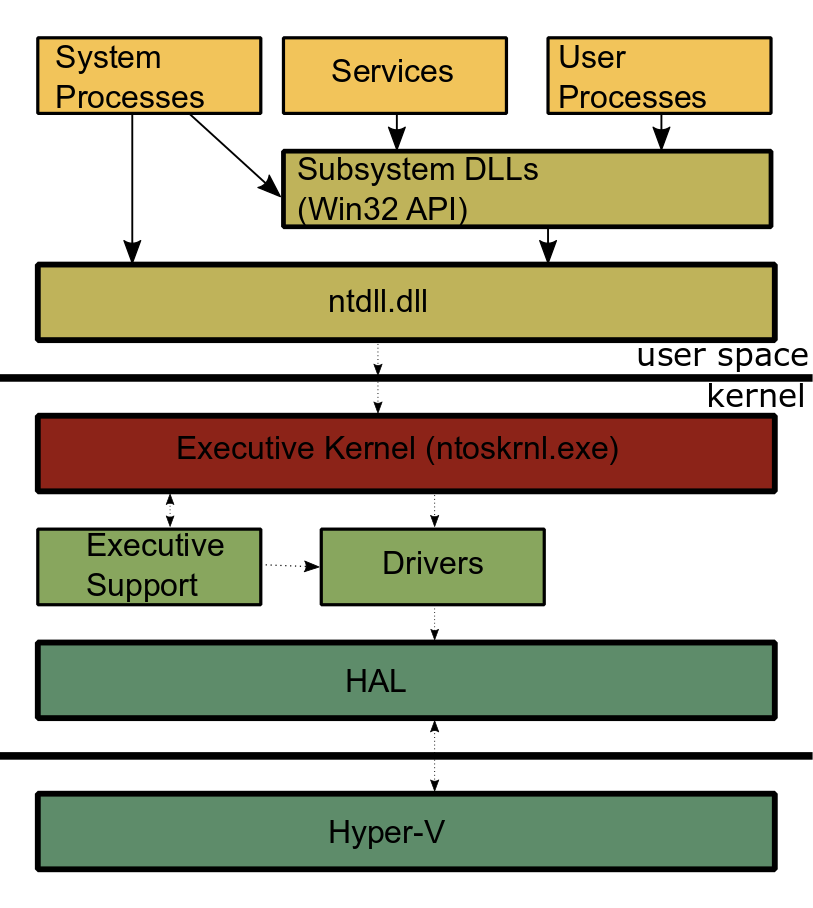

This how Windows looks like when you cut it open: Starting at the top there are the system processes like winlogon.exe or the session manager smss.exe that do essential user space operations. Next are the services doing all the things services do (printing, sound etc.) and the 'normal' user mode processes.

This can be looked at using the Process Explorer from the Sysinternals toolkit (https://www.google.de/search?q=sysinternals+site%3Amicrosoft.com). The Sysinternals Suite is a collection of tools created by Mark Russinovich, the author of the windows internals books. It does what it says in the title: help look at system internals and it is definitely useful to have around while trying to figure out how windows works.

Subsystem dlls and ntdll.dll

Like I said in the syscall explanation you need to use a special mechanism to access kernel functions. But you are not supposed to do even that directly. There are two layers of abstraction in the user mode that make your (and windows') life easier.

First there are the windows subsystem dlls. This is pretty much the Windows API, often still called Win32 Api: kernel32.dll, user32.dll and so on. The 32 is just for misdirection, they all support 64-bit architecture.

And second there is ntdll.dll which implements the interface to the kernel. As you can see in my diagram certain system processes use the ntdll function directly and any user-mode application could technically do so as well. But since they aren't officially documented and there is no guarantee they won't change suddenly it isn't recommended unless you really know what you are doing.

Kernel

On the kernel side is the other side of this interface that receives the syscalls and forwards them to the corresponding kernel-mode functions. The kernel itself can be divided into executive part (executive functions), executive support (support functions) and drivers ( modules loaded into the kernel to interface with special hardware, often vendor specific). And while the distinction is useful don't get too hung up on it: different people will divide the windows kernel into different parts, even so far as to say the real kernel is just a small part of really core functionality inside the Kernel Mode.

HAL, Hypervisor

It would be nice to have a HAL-9000 hidden in every Windows OS but HAL really just stands for 'Hardware Abstraction Layer' and that is all I know about it. And below the HAL there could be a hypervisor. Completely apart from the whole virtual machine thingy windows uses the Hyper-V hypervisor as an additional privilege level to hide away security functionality. Google for 'windows virtualisation based security' if you want to know more. This is really outside the scope of my tutorial, at least for the foreseeable future.

Processes and Threads

As you should know all programs, service etc. running on windows are organised as processes which in turn contain one or several threads used for scheduling((The art of distributing processor time to all threads running in the system.)). I won't go into details here because we will look at processes (and maybe at threads) using Windbg in Part 4.

Memory Management

Every windows user space process has his own virtual private address space from 0x000'00000000 to 0x7FF'FFFFFFFF. Which doesn't mean that every process can use 8TB of memory it just means that the memory of every process (stack, code etc.) sits somewhere in that address range and we have already seen that in Windbg.

The mapping between virtual memory and actual physical memory is done via 'pages'. That are blocks of a certain size in virtual memory that correspond to blocks of the same size in physical memory, or that could be swapped out to the hard disk if physical memory runs out. See the wikipedia page table page (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Page_table) at least for the picture and if you want for more details on how this works.

The kernel has it's own virtual address space from 0xFFFF0800'00000000 to 0xFFFFFFFF'FFFFFFFF. We also saw that in Windbg already and that is why we always know if we are inside kernel or user space. And like the user space processes the kernel doesn't 'begin' at virtual address 0xFFFF0800'00000000 it just sits somewhere in that range. One reason for that is a security feature called 'Address space layout randomisation' (ASLR) or rather Kernel ASLR in that case.

And the last thing I will mention in this quick rundown are 'paged pool' and 'nonpaged pool'. Like I said every memory page can be copied to the hard disk if physical memory is running low. But it would be very stupid if an important system function, lets say.. the mouse driver(!) would have to wait for his memory to be copied from the hard disk back to physical memory until he could process that the user moved the mouse. So inside the kernel there is a nonpaged memory pool with pages that will never be moved to the hard disk.

Objects and handles

This is about how various 'things' are represented inside the windows operating system: you might have guessed it - as objects. Each process is represented by a process object, each file by a file object, each event by an event object.. you may see a pattern evolving there. Each object consists of an object header and an object body. The header is used by the Object Manager for ..? object management and contains things like name, type, security descriptor etc. and the body contains the actual object attributes. That means the body is different for each type (process, file, etc.) of object.

Apart from type all objects fall into two categories: Kernel and Executive objects. Kernel objects are only used internally by the kernel while executive objects are accessible from user-mode. Each executive object contains one or more kernel objects.

Related to object are handles. If a user requests access to a file the kernel create a file object and gives the user access to it, so he can use it to read from the file or whatever. But the kernel doesn't hand over a pointer to the object but a handle. This handle is simply a number that can be used to access the object via the handle table. Reasons for this are once again security, stability and all that. It also simplifies 'garbage collection' (using the term loosely): if all handles pointing to a certain object are closed the object itself can be destroyed.

We will look at object and handles more closely in Part4b: processes.

Linked Lists

Not really a deep and complicated secret but the windows kernel uses a special kind of linked list to chain things, for example objects) together and if you debug around the kernel you will stumble upon them a lot. I won't go into details here: If you understand the concept of linked (pointer) lists just read the Microsoft article on the "LIST_ENTRY structure". If you don't go and read a writeup on linked lists in c or c++ and then read the Microsoft article on the "LIST_ENTRY structure".

Last words

You made it: you now know how windows is structured and how it does certain things. This is all we need to know to switch back to Windbg and try to poke around a bit. If you want to know more you could try to search around the interweb but in my opinion there is no real alternative to reading the 'Windows Internals' books by Mark Russinovich (and others). But be careful: once you start reading those nothing will ever be simple again! You have been warned.