Next: 5: Windbg scripts

4d: Syscalls

Content

-

System calls

-

User space vs kernel space debugging with a kernel debugger

-

Analysing assembly code

We will continue the "workshop" style and take a closer look at syscalls. There will be nothing revolutionary, but we are moving ever further towards undocumented behaviour. To fully understand the syscall mechanism you will need quite a bit of assembly knowledge and the endurance to investigate assembly code. And while it may seem pretty academic this chapter has practical applications: hooking the syscall table is still a thing that rootkits and antivirus solutions do.

Hooking

Hooks are a mechanism to intercept events: messages, keystrokes and so on. And they are totally legal: for example a keyboard macro software may hooks into the keyboard driver stack to record or play macros. But in the same way a rootkit may hook into the keyboard driver stack to record password keystokes. And using the general idea it is possible to hook into all sorts of system functions. Like into the syscall table so every call to a specific system function causes custom code to be executed before the original system function. Which is one of the main ideas behind rootkits. If you can't trust system function like "read-file" to do what they are supposed to do you do not own your operating system any more, someone else does.

Looking for syscalls

If you remember my "Windows Architecture" picture from part 3 "ntdll" is the last thingy in user mode before the user/kernel transition, so let's look there:

x ntdll!ntopen*

Should return absolutely nothing useful. That is because we are trying to debug the user mode from a kernel debugger. What we need to do it get into the context of a process using '.process' with '/r' to reload user mode symbols and continue from there. My explanations are based on notepad because I am fairly certain I can use it to trigger an "OpenFile" syscall. If you are confident feel free to use whatever process or syscall you like.

!process 0 0 notepad.exe

.process /r <process address>

x ntdll!ntopen*

..

00007ff9b0590490 ntdll!NtOpenFile

...

So there really is a ntdll!ntOpenFile function. Let's take a closer look:

// Windows 10 1709. This may vary considerably on a different version.

kd> uf ntdll!NtOpenFile

ntdll!NtOpenFile:

00007ff9b0590490 4c8bd1 mov r10,rcx

00007ff9b0590493 b833000000 mov eax,33h

00007ff9b0590498 f604250803fe7f01 test byte ptr [SharedUserData+0x308 (000000007ffe0308)],1

00007ff9b05904a0 7503 jne ntdll!NtOpenFile+0x15 (00007ff9b05904a5) Branch

ntdll!NtOpenFile+0x12:

00007ff9b05904a2 0f05 syscall

00007ff9b05904a4 c3 ret

ntdll!NtOpenFile+0x15:

00007ff9b05904a5 cd2e int 2Eh

00007ff9b05904a7 c3 ret

The function is rather short. Which is good for us because we can exercise our assembly knowledge to find out exactly what is going on.

What is going on?

-

Rcx is moved into r10.. no apparent clue what that is about.

-

A hex 33 is moved into eax. Guess what we will find if we google "Windows Syscall table" (this one for instance: http://j00ru.vexillium.org/syscalls/nt/64/) and look for

0x33: NtOpenFile. -

Next there is a bit of code that decides weather to use the old

int 2ehor the newsyscallmechanism:- Test compares some memory location with 1 and if those are different the jne (Jump Not Equal) jumps to the

int 2ehbranch, right? - Unfortunately it is the other way around, try to find out why

- Test compares some memory location with 1 and if those are different the jne (Jump Not Equal) jumps to the

Why??

-

Let's assume the byte pointer points at a variable with value 0 (it does for me)

-

Test does a logical AND: If the variable is 0, the result is 0 and the zero flag is set

-

jne is the same as jnz (Jump Not Zero) and will jump if the zero flag is cleared

-

This means it doesn't jump and we end up at

syscall

The actual system function

It's a bit cheating, but either by using google or searching through the kernel symbols we can use the kernel function that our syscall is calling: nt!ntOpenFile. We can even find the function documentation on MSDN, since drivers have to use this function directly from the kernel without calling the ntdll!ntOpenFile stub. The question we are here for is: how does the syscall number from the ntdll function translate into the call to nt!ntOpenFile?

Breaking into user mode

Breaking into a user mode process from the kernel debugger can be a bit tricky. Ideally you have to get into the correct process context with .process and add the process address to your breakpoints. The /p option forces Windbg to translate virtual to physical addresses so you can access the correct memory.

!process 0 0 notepad.exe

.process /p /r <process address>

bp /p <process address> ntdll!ntopenfile

g

Trying to open a file (or doing pretty much anything involving gui windows) should trigger the breakpoint. If it doesn't you can try to restart everything or just apply additional force. With .process /i <address> you can debug the process invasively by forcing the debugee into that process. Windbg will instruct you that you have to continue execution and will immediately break again inside the process. Now set the breakpoint and it should work. The command sxe ld:notepad` will do roughly the same by setting an exception on notepad 'load'. You have to execute it before starting notepad and will be dropped into the process on one it loads.

It may need some playing around but eventually you should bread at the start of ntdll!ntopenfile. Then you can use step into/trace to follow the code and watch how it goes right over the syscall instruction. Unfortunately we can't watch the actual syscall mechanism at work. Even if they (AMD/Intel and Microsoft) would let us it would just crash the system anyway. So in order to look further we have to branch out a bit and try to find out what happens on the internet. You can find some bits and pieces around the web, but the most straightforward source of information is AMD's "AMD64 Architecture Programmer’s Manual, Volume 2: System Programming".

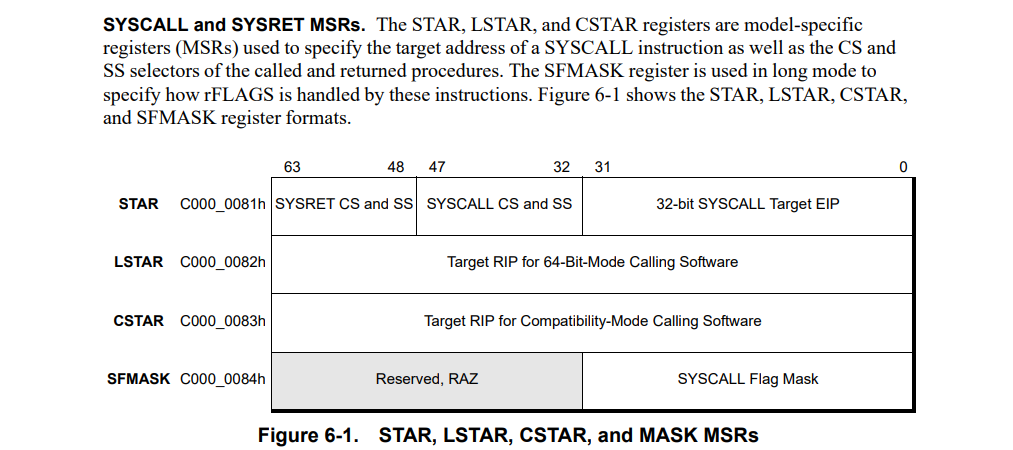

It explains a lot of technical details about the syscall instruction including that MSR C0000082h contains the address the syscall is supposed to jump to. If you read the address from the MSR register and dissasemble that location you should get the code of nt!KiSystemCall64:

How to get the syscall destination from a MSR register

:::cpp

kd> rdmsr C0000082

msr[c0000082] = fffff8026858ca80

kd> uf fffff8026858ca80

Flow analysis was incomplete, some code may be missing

nt!KiSystemCall64:

fffff8026858ca80 0f01f8 swapgs

fffff8026858ca83 654889242510000000 mov qword ptr gs:[10h],rsp

fffff8026858ca8c 65488b2425a8010000 mov rsp,qword ptr gs:[1A8h]

fffff8026858ca95 6a2b push 2Bh

fffff8026858ca97 65ff342510000000 push qword ptr gs:[10h]

fffff8026858ca9f 4153 push r11

fffff8026858caa1 6a33 push 33h

fffff8026858caa3 51 push rcx

fffff8026858caa4 498bca mov rcx,r10

fffff8026858caa7 4883ec08 sub rsp,8

fffff8026858caab 55 push rbp

fffff8026858caac 4881ec58010000 sub rsp,158h

...

Setting a breakpoint on KiSystemCall64 will just crash the debugee. Which shouldn't come as too big a surprise. While we can single step through certain parts of the kernel, we can't just stop vital parts of the debugee's operating system without crashing it. That would require some sort of hardware debugging or a full system emulator like QEMU.

So we will have to figure out what happens from the assembly code. Which is a pretty daunting task, since there is a lot of assembly to crawl through. But we don't want to understand all of it (At least I don't.. I would likely die of old age before that), we just want to understand how our syscall number results in the call to the correct system function.

Understanding KiSystemCall64

There is no reason to look at assembly code exceeding a few lines in Windbg. At the very least copy the code into your favourite text editor. Notepad++ for instance gives you syntax highlighting and can highlight search results so you can find out where a certain register is uses quickly. If you want to do get deeper into it and maybe skip my guidance altogether I would suggest you use a dissembler with a graph view like Ida or Radare.

In theory what we are looking for could be pretty simple. The syscall number is used as index to an array called "System Call Table" or or something and that array contains pointers to all the actual system functions. Unfortunately it isn't that simple and the reason is most likely security((With Microsoft you can never know for sure. Maybe they just want to annoy people that do kernel research.)). But there still has to be some sort of table lookup and a call so the actual system function.

And we have a few bits and pieces of information we can use:

-

rax contains the system call number

-

rcd, rdx, r8 and r9 and the stack contain the parameters

Hint

Don't get distracted by all the assembly code. Most calls go to specific locations. You are looking for a call to a register or variable. While it technically could be a jump instruction that's unlikely: we are looking at the assembly of c or c++ code and we can expect it to conform to certain conventions.

Solution

{{:tutorials:winkdbg:kisyscall64_call.png?direct&600|}}\ and\ {{:tutorials:winkdbg:kisyscall64_call2.png?direct&600|}}\ If you backtrack how they are called or cheat with Ida you can see that it doesn't really matter which one is called and that the first one is likely a special case for system functions without any parameters. \ {{:tutorials:winkdbg:kisyscall64_call_ida.png?direct&600|}}\

Hint

This one is a bit tricky. Once again try to ignore most of the assembly code and just follow the clues:

-

The thingy we are looking for may be called somethingTableSomething

-

It should be a pointer to an array or a pointer to a structure that contains an array.

-

The syscall number that is initially in rax has to be used together with the table

-

The resulting function address has to end up in the function call from Exercise 1: r10

Solution

The only thingy called table is nt!KeServiceDescriptorTable. It also get's involved with the system call number from rax and the r10 register.

0: kd> dp nt!KeServiceDescriptorTable

fffff801c8c9e880 fffff801c8bd7c50 0000000000000000

fffff801c8c9e890 00000000000001cc fffff801c8bd8384

fffff801c8c9e8a0 0000000000000000 0000000000000000

fffff801c8c9e8b0 0000000000000000 0000000000000000

Doesn't look like an array. Let's browse around:

``` cp

0: kd> dp poi(nt!KeServiceDescriptorTable) L30

fffff801c8bd7c50 fdbb9940fd081b44 0393f3c001407302

fffff801c8bd7c60 fe1cc90001bafe00 01abfe0601ad1f05

fffff801c8bd7c70 01ba6d0101add105 01b47c4001104500

fffff801c8bd7c80 01c4f60001413b00 01e6ed0002043800

fffff801c8bd7c90 01ab500101819601 01986a02020c02c0

fffff801c8bd7ca0 0213024001c9ed00 01dacf0201da7e01

fffff801c8bd7cb0 01ce550101bcc002 021a4e05021d3501

fffff801c8bd7cc0 018101c301c2c600 0389864001c03400

fffff801c8bd7cd0 01e70f0101103700 01bbe78202109e00

fffff801c8bd7ce0 01af430101d26e00 fd0f440101d40800

This looks more like an array. It is called nt!KiSystemServiceTable and it is what we are looking for.

Those numbers aren't kernel addresses but as I said already it's not that easy. We just have to find out how they are translated into kernel addresses.

Side note: There is a lot more going on, but once again I will ignore most of it and try to keep things "simple". Apart from the number of system calls (0x1cc in my case) the KeServiceDescriptorTable contains another array. And there is also KeServiceDescriptorTableShadow. Feel free to research those as well.

</div></details>

{::nomarkdown}

<div class="message is-info">

<div class="message-header">

<p>Exercise 3</p>

</div>

<div markdown="1" class="message-body">

Find out how the system function address is calculated from the values in the KiSystemServiceTable. Check the hint for the relevant parts of assembly code if you don't have Ida/radare or lot's of time.

</div>

</div>

{:/nomarkdown}

<details><summary>Hint</summary><div markdown="1" class="notification is-dark">It boils down to this:

``` asm

...

nt!KiSystemServiceUser+0xe5:

...

mov edi,eax

shr edi,7

and edi,20h

and eax,0FFFh

...

KiSystemServiceRepeat:

lea r10, KeServiceDescriptorTable

...

mov r10, [rdi+r10]

movsxd r11, dword ptr [r10+rax*4]

mov rax, r11

sar r11, 4

add r10, r11

cmp edi, 20h

jnz short loc_140187F30

...

call r10

...

Solution

mov edi,eax

shr edi,7

and edi,20h

This instruction mov edi,eax bugged me at first. Why access the 32 bit registers? I was following the expectation that this would only write to the lower 32 bits of the rdi register, much like writing to AX or AL only writes to the lower 16- or 8 bit or rax. But it works differently. Writing to the lower 32 bit registers (eax, edi, e..) will clear the upper 32 bits. As for the rest the shift right and and instruction will result in zero for anything below 0x1000. So for the scope of this workshop we can assume that rdi is zero for the next block.

mov r10, [rdi+r10]

movsxd r11, dword ptr [r10+rax*4]

mov rax, r11

sar r11, 4

add r10, r11

This is (the dirty secret) how the ServiceTable is accessed: the syscall number in rax is used as index into an integer (32-bit) array. The value at that index is shifted right by 4 bit and added to the base address of the ServiceTable. The resulting address is the address of the corresponding system function. Try it out:

0: kd> dd nt!KiServiceTable+4*33 L1

fffff801c8bd7d1c 01d37002

0: kd> ? 01d37002 >> 4

Evaluate expression: 1914624 = 00000000001d3700

0: kd> u nt!KiServiceTable + 001d3700

nt!NtOpenFile:

fffff801c8dab350 4c8bdc mov r11,rsp

fffff801c8dab353 4881ec88000000 sub rsp,88h

// As one liner:

0: kd> u nt!KiServiceTable + ( @@c++(((int*)@@(nt!KiServiceTable))[0x33])>>4 )

nt!NtOpenFile:

fffff801c8dab350 4c8bdc mov r11,rsp

fffff801c8dab353 4881ec88000000 sub rsp,88h

Now what?

We made it. You should know have a general idea how the windows syscall mechanism works. You should have improved (or proved) your AMD64 assembly knowledge. And you experienced some "design principles" you may see again in various places of the windows kernel: the combined tables, the bit shifting and calculating kernel addresses based on a base address.

Like I mentioned already I ignored substantial parts of KiSystemCall64. Feel free to explore those on your own or continue with the next chapter.